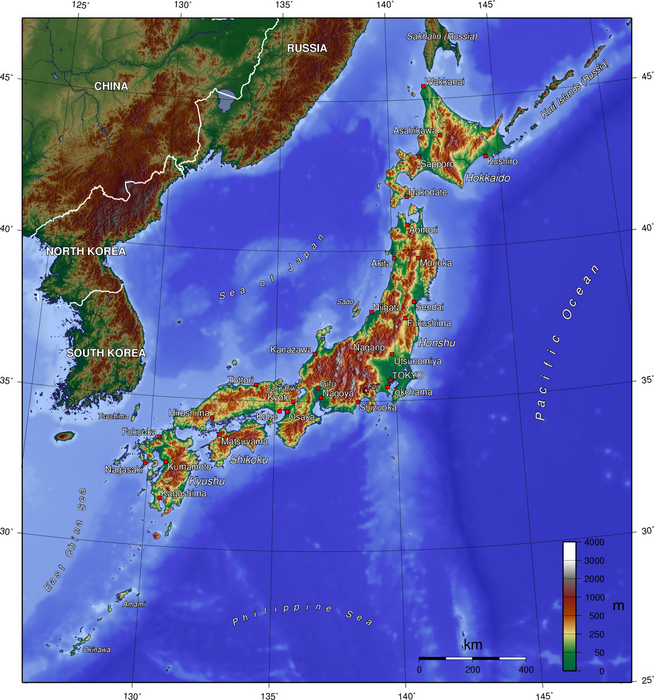

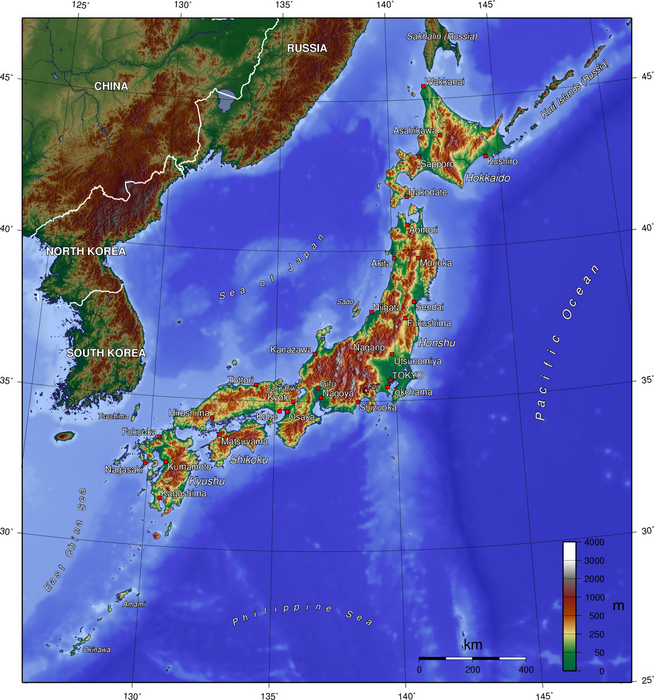

Topographical map of Japan (source: Wikipedia Commons)

Catherine Knight

Abstract

Owing to its diverse geology, geography and climate, Japan is a country rich in biodiversity. However, as a result of accelerated development over the last century, and particularly the post-war decades, Japan’s natural environments and the wildlife which inhabit them have come under increased pressure. Now, much of Japan’s natural forest, wetlands, rivers, lakes and coastal environments have been destroyed or seriously degraded as a consequence of development and pollution. Despite increasing awareness of the importance of preserving Japan’s remaining natural environments and wildlife, habitat destruction (both direct and indirect), inadequately controlled hunting, and introduced species pose a threat to these. This paper explores these factors, and the underlying forces—political, legislative and economic—which have undermined efforts to preserve Japan’s natural heritage during the post-war decades.

Introduction

This article outlines the state of Japan’s natural environments and wildlife, and assesses the key threats to habitat destruction, hunting and introduced pests. It then examines the key factors—political, legislative and economic—which contribute to Japan’s failure to adequately protect wildlife and natural environments from these threats, and in particular, the primary threat of habitat destruction.1

It will be seen that the key factors are the relative weakness of the legislative framework for nature conservation; a system for managing national parks that emphasises tourism rather than the ecological function of parks; and the strong impetus for development, particularly in rural areas, which undermines attempts to protect natural environments and the wildlife which inhabit them.

It should be emphasised that Japan is not alone in struggling to adequately protect its natural heritage—this is a problem faced by many nations around the world. Also, considered in the context of its long period of human occupation and very high population density, it might be suggested that it is remarkable that Japan has retained as much of its natural environments as it has.2

The state of Japan’s natural environments and wildlife

The Japanese archipelago consists of almost 4000 islands with a combined coastline of approximately 33,000 kilometres (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) 2002: 136). Japan’s topography is characterised by mountainous regions, which cover 75 per cent of the land area. Before human activity impacted on the environment, Japan was for the most part covered in forest: subtropical forest in the southern part of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, as well as the southern islands; temperate forests through the remainder of Honshu; and boreal forests in Hokkaido and the highlands of Honshu. On flatter ground, in river valleys or natural basins, bog vegetation predominated: consisting of rushes, grasses and small trees (Bowring & Kornicki 1993: 13–14). There was a complex network of fast-flowing rivers across the archipelago, feeding into numerous lakes.

Japan’s geographical isolation, diverse topography and climate has supported a high level of biological diversity. About 200 mammal species have been identified in Japan, compared to 67 in the United Kingdom and Ireland, an area roughly similar in size. Over 700 bird species, including sub-species, have been recorded, again approximately double the number found in United Kingdom and Ireland (Environment Agency 2000: vol.1, 285; Kellert 1991: 298).

Mixed coniferous and regenerating indigenous forest in Tohoku (Photo: C. Knight)

Today, about 67 per cent of Japan’s land area is forested, however a large proportion of that—about 40 per cent—is coniferous plantation forest (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2006: 19, 255). Of the remaining natural (non-plantation) forest, only a small percentage is primeval forest, and the area of primeval forest continues to decrease (OECD 2002: 135–136). Wetlands cover approximately 50,000 hectares (0.13 per cent of Japan’s land area), but many of these are threatened by water pollution and land reclamation projects (OECD 2002: 149; Nature Conservation Society of Japan (NACSJ) 2003). Most major rivers have been modified with dams, dykes, concrete embankments, and straightening works. Nagara river, the last free-flowing river in Honshu was dammed in 1994 (McCormack 1996: 46).

Only 45 per cent of the coastline of the four main islands remains in an unmodified state – the rest has been transformed by land reclamation, dredging, construction of port facilities, seawalls, breakwaters and other shoreline protection works (OECD 2002: 136, Nature Conservation Society of Japan (NACSJ) 2003).

Many of Japan’s lakes and rivers are polluted: for example, in 2005, the level of pollution of 47 per cent of all lakes exceeded environmental standards (Ministry of the Environment 2007). In the same year, the level of pollution of 24 per cent of Japan’s coastal waters exceeded environmental standards, and enclosed areas in particular, such as the Seto Inland Sea, Ise Bay and Tokyo Bay are seriously polluted by household and industrial waste (Ministry of the Environment 2007).

Concrete "tetrapods" on the Fukushima coast, used to minimise erosion (source)

Data from the “red data lists” compiled by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment (MOE) provide an indication of the state of Japan’s native flora and fauna. The red data list, a list of endangered species, was first compiled by the Environment Agency in 1991 and subsequently updated according to IUCN (World Conservation Union) criteria.3 Of the approximately 200 mammal species, the red list currently lists 4 as extinct, and 48 as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable. Of about 700 bird species, it lists 14 as extinct or extinct in the wild, and 89 as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable. Of about 300 fresh or brackish water fish species, it lists 3 as extinct, and 76 as critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable (MOE 2006).

Threats to Japan’s natural environments and wildlife

The three primary threats to Japan’s natural environments and wildlife are habitat loss and degradation, poorly-controlled hunting, and introduced species. Habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation is undoubtedly the most serious threat to Japan’s wildlife and natural environments. There are two aspects to habitat loss in Japan: failure to protect habitats (through legislative measures and conservation management practice), and direct habitat destruction, such as deforestation, land reclamation and pollution.

One key problem in Japan is the level of protection provided for flora and fauna in areas designated as national or natural parks. Japan has 29 national parks, covering 5.4 per cent of its land area (MOE 2008a).4 To compare with countries of similar size, the United Kingdom has 14, comprising nearly 8 per cent, Korea has 17 (6.6 per cent) and New Zealand 14 (11. 5 per cent). Therefore, as a percentage of land area, this is less (though not significantly less) than in similarly sized nations (United Kingdom, Korea and New Zealand), while more than larger countries such as the United States and Canada, whose national parks (but not necessarily “protected areas” comprise about 2 per cent of their land areas.

However, little of the national park area in Japan is protected from environmentally detrimental development or human activity. The Natural Parks Law, which governs the management of these areas, does not preclude development, construction, or other human activities that may detrimentally impact on the parks’ environments. In fact, development of tourist facilities in national parks is explicitly encouraged by the Resort Law (1987). Furthermore, the designation of these areas as national parks in itself brings about environmentally damaging impacts as a consequence of high traffic volumes, excessive numbers of visitors, and the construction of tourist facilities and roads.

To date, only a negligible proportion of natural park area has been designated as reserves in which human activity is strictly controlled: only five areas totalling 5,631 hectares (0.015 per cent of the total land area of Japan) have been designated as “wilderness areas”—areas where “activities entailing adverse effects on ecosystems are strictly prohibited”. In addition to these, about 95,000 hectares have been designated as national or prefectural “conservation areas”—areas in which human activity is limited but not prohibited outright (Environment Agency 2000: vol.2, 144). Combined, the total area of conservation land in which human activity is controlled makes up 0.27 per cent of Japan’s total land area.5 However, even in these areas, inadequate staffing and resourcing levels means that there is not always effective monitoring to ensure that prohibited activities do not take place.

In addition to the failure to protect areas of ecological importance, direct habitat destruction is a major threat to natural habitats. Habitat destruction has taken many forms: deforestation; land reclamation; construction of dams and other riparian works; use of pesticides on agricultural land; development projects; and pollution.

Red-crowned cranes of Hokkaido—the last remaining population in Japan (source)

Deforestation had already taken a toll on Japan’s wildlife by the Meiji period (1868–1912), particularly in Honshu, pushing a number of species, such as the Japanese wolf (Canis lupus hodophylax) and the Japanese red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis), to extinction or to the brink of extinction (Stewart-Smith 1987: 127; Knight 1997).6 Extensive logging of indigenous forest and afforestation with single-species tree plantations has destroyed or degraded the forest habitat for many forest dwelling species, particularly in the post-war era. When reforested with commercial plantations, the monocultures of planted trees allow few indigenous plant species to colonise, and have little to offer animals such as the macaque (Macaca fuscata), Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus), and the Japanese serow (Capricornis crispus, an antelope-like ungulate) (Stewart-Smith 1987; Maita 1998: 38–44; Hazumi 1999; NACSJ 2003; Knight 2003: 35–36; 119–120; 160). To adapt to their depleted habitat and food sources, these species have changed their behaviour to include eating shoots of young plantation trees and the raiding of farm crops (Hazumi 1999: 208; Knight 2003: 191–192). This makes them vulnerable to being culled as agricultural and forestry pests.

Land reclamation projects have claimed 60 per cent of Japan’s tidal flats, half of Japan’s seacoast and about one-third of its wetlands, mainly to reclamation for agricultural, industrial and commercial use (NACSJ 2003; Danaher 1996). Dams have been constructed in every major river in mainland Japan, causing degradation of the river environment and impacting on fish populations by obstructing water and sediment flow, impeding animal movement, fragmenting riverine habitats, and degrading water quality (McCormack 1996: 45–48; McCormack 2007: 448; Niikura & Souter n.d.). By the late 1990s, only 12 of 113 major rivers surveyed were free of river crossing structures or had facilities permitting sufficient fish passage. As a result, species of freshwater fish that need to migrate for breeding purposes have declined significantly (OECD 2002: 136).

Nagara River, the last major river in Japan to be dammed - then and now. Top: As portrayed by Eisen in the 19th century. Bottom: Now - the “estuary barrage” at the mouth of the river (Wikipedia).

The intensive use of agricultural chemicals since the Second World War has caused contamination of soil and waterways, and has made farmland, marshland and other lowland areas uninhabitable for a number of species, causing the extinction of some, including the Japanese crested ibis (Nipponia nippon).7 Fertiliser and pesticide application levels in Japan are higher than those in almost all other OECD countries, partly because of the relatively hot, wet climate and intensive cropping, although it has been decreasing in line with overall reduction of crop production over the last decade (OECD 2002: 139).

Development projects, such as roads, airports, resorts and exposition sites, particularly in areas of ecological importance, have destroyed, degraded or fragmented many natural environments.8 For example, road infrastructure increased by almost 40 per cent in area and 80 per cent in length in the 1980s and 1990s, causing fragmentation and interference with adjacent ecosystems (OECD 2002: 135). Further, while about five per cent of Japan’s total land area has been designated as national parks, much of this land is affected by extensive development, such as roads, dams and resorts.

In the Ryukyu Islands (a sub-tropical island archipelago south-west of mainland Japan), large expanses of coral reef habitats have been destroyed due to agricultural chemical run-off, river improvement works, and soil erosion from construction sites, mainly for resorts and airports (McGill 1992; NACSJ 2003). For example, 95 per cent of the coral reefs of Okinawa (part of the Ryukyu archipelago) have been reported to be dead or dying as a result of heavy soil runoffs caused by resort development and the clearing of land for agriculture, and in 2002, fewer than ten per cent of coral communities in the waters surrounding the Ryukyu Islands were classified as healthy (McGill 1992; OECD 2002: 136). The situation has subsequently further deteriorated as illustrated by the case of the assault on the Awase Wetlands (Urashima 2009).

The second primary threat to wildlife is poorly regulated or controlled hunting. Animals are hunted (or culled) in Japan for a number of reasons: as agricultural or forestry pests, to protect human safety; as game; and for economic gain (often illegally, as in the case of bears illegally hunted for their gall bladders and other parts). The hunting of larger animals such as the brown bear, Asiatic black bear, wild boar and Japanese macaque has increased over the last decades in response to the increased competition between humans and wildlife for space and food. This conflict has grown steadily throughout the long twentieth century, particularly during, and in the years following, the Second World War, when vast areas of natural forest were cut down and replaced by monoculture plantation forest, farms, roads, ski resorts and other development (Stewart-Smith 1987: 74–78; Anon. 1994, 30, 3; Hazumi 1999: 208; Maita 1998: 38–44; Knight 2003). In an effort to find food in their rapidly declining habitats, animals increasingly encroach on to farm and forestry land, and rural villages or towns, leading to increased culling.

Asiatic black bear (Photo: Scott Schnell)

The situation of the Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus (Japonicus)) illustrates this relationship between habitat destruction and increased culling. In the early 1900s it was widely distributed throughout the three main islands of Japan, particularly in forested areas away from human settlements. However, human disturbance of many bear habitats grew marked from the 1940s, mainly in the form of increased forestry activity (Hazumi 1999: 208). This has forced bears out into plantation forest or farming areas where they cause damage by stripping bark or feeding on fruit and other crops, with the result that they become more vulnerable to being targeted as pests. This leads to culling of “nuisance bears”: on average, more than 2,000 bears are culled annually (of an overall estimated population of between 10,000 and 15,000), though in years of high levels of bear damage, a far greater number are culled. In 2006, for example, 4,500 were culled (Yomiuri Shinbun December 19, 2006). Bear “harvest” rates (human-caused fatalities through either hunting or culling) are not regulated according to biological data on the species, and in fact, harvest numbers have been increasing, despite a decreasing overall population (Hazumi 1999: 209).

The brown bear of Hokkaido (Ursos arctos yesoensis), one of the few remaining populations of brown bear in Europe and Asia, is under similar pressure. Its population is estimated at about 3,000, and about 250 bears are killed annually (Mano & Moll 1999: 129). The rapid decline of two localised bear populations has led to their designation as endangered subpopulations—however, the population as a whole remains unlisted, and the bear is considered a game species under the Wildlife Protection and Hunting Law (Mano & Moll 1999: 128). The most urgent threat to the remaining population is excessive control killing—it has been predicted that if the current level of control killing is sustained, the Hokkaido brown bear population will become extinct (Tsuruga, Sato & Mano 2003: 4). Habitat fragmentation, caused particularly by the construction of forestry roads, is an additional pressure on the remaining population.

The law which regulates hunting in Japan is the Wildlife Protection and Hunting Law, which took its current form (revised from the Hunting Law) in 1963 (See Table 1.) The purpose of the law is “to protect birds and mammals, to increase populations of birds and mammals, and to control pests through the implementation of wildlife protection projects and hunting controls”. The law gives the Ministry of the Environment (MOE) the authority to specify game species (which can be subject to hunting), of which there are 29 bird, and 17 mammal species. It also allows for the designation of areas in which hunting is prohibited, hunting periods, harvest limits, and hunting methods. Under the law, hunters must obtain a hunting license and register with the prefecture in which they intend to hunt. However, monitoring compliance is largely the responsibility of volunteers called chōju hogoiin (wildlife conservators), the majority of whom are selected from local hunting associations (ryōyūkai)9 (Yoshida 2004: personal communication), a system in which there is obvious potential conflict of interest.

Overhunting is a problem for many species, particularly those which cause crop and forestry damage such as the bear, due to the perception that the populations are increasing and culling is therefore necessary. In fact, it is more likely that populations are decreasing (local and national population figures are only approximate estimates), but the level of contact with humans is increasing due to habitat fragmentation and degradation, and the attendant changes in wildlife behaviour, particularly in feeding habits (Hazumi 1999: 210). In addition, poaching is widespread in Japan, especially for animals such as bears, whose parts command high value, both on national and international markets, largely as medicinal products (Mano & Moll 1999: 129–131; Hazumi 1999: 209). However, authorities have made little attempt to control poaching (Hazumi 1999: 209).

Invasion of natural habitats by alien species is a further factor putting pressure on indigenous species, particularly in unique island environments. Introduced species including raccoon, weasel, marten, common mongoose, black bass and bluegill, disturb ecosystems through predation, occupation of habitats and hybridisation. For example, the black bass, which can grow to 87 centimetres in length and weigh up to 10 kilograms, was introduced in 1925 and has now spread throughout Japan’s waterways. A few bluegill, introduced in 1960, have also spread widely throughout the country. These fish are putting pressure on the populations of native species, such as the southern top-mouthed minnow, deep crucian carp, and the northern and flat bitterling (OECD 2002: 135; Watanabe 2002).

The risk of introduced species significantly changing endemic biota and ecosystems is especially high on islands such as Amami and Okinawa, which are isolated from other regions and are habitat to a large number of endemic species (OECD 2002: 135). Several threatened species are known or expected to be negatively affected by the introduction of predators (primarily for snake control) to these islands. On the Izu Islands, the introduction of the Siberian weasel (Mustela sibirica) to Miyake-jima in the 1970s and 1980s appears to have caused significant declines in Japanese night-herons (Gorsachius goisagi) and Izu thrushes (Turdus celaenops). On Okinawa, feral dogs and cats and the introduced Javan mongoose (Herpestes javanicus) and weasel (Mustela itatsi) are predators of Okinawa rail (Gallirallus okinawae), Ryukyu woodcock (Scolopax mira) and Okinawa woodpecker (Sapheopipo noguchii), while feral pigs damage potential ground-foraging sites for Okinawa woodpecker (Birdlife International n.d.; McGill 1992).

The role of government and legislation in nature conservation in Japan

There have been few legislative measures for the protection of wildlife and natural habitats until recently, and even today, Japan is criticised for the gap apparent between its stated policy objectives and the general trends over the past two decades—the ongoing destruction of important habitats, particularly natural forests and wetlands, and the continued endangerment of many plants and animals (OECD 2002: 132). Recent decades have also demonstrated that even if a species is recognised as severely threatened, government policy and practice often falls well short of proactive protection of these species and their habitats. Indeed, as will be seen later, government-sponsored development projects frequently act to increase the threat to wildlife and their habitats. There are also tensions between the concerns and needs of (particularly rural) citizens and the interests of nature conservation, as can be seen in development projects aimed at “regional rejuvenation”.

Until recently, there has been only a limited legislative framework for the protection of threatened species or their habitats, and conservationists argue that the current framework remains weak. The first government agency solely concerned with environmental management, the Environment Agency, was established in 1971, and in the following year, the Nature Conservation Law was enacted, which provided a basic framework for subsequent legislative measures and policy relating to nature conservation. Subsequent to the law being enacted, a limited number of areas were designated as “wilderness areas” and “nature conservation areas”, affording more protection than national park areas. However it was not until 1992 that the Law for the Conservation of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Japan’s first domestic law for the protection of endangered and threatened species, was enacted. The law allows for the designation of natural habitat conservation areas, sets limits on the capture and transport of endangered species and establishes guidelines for the rehabilitation of endangered natural habitats (OECD 2002: 58).

Summary of laws/events relating to nature conservation in Japan

While undoubtedly a positive step for wildlife conservation, the effectiveness of the law is limited by the fact that the MOE lacks sufficient power to designate endangered species as protected species or to designate important habitats as protected areas (Yoshida 2004: personal communication). A further problem inherent in the law is that while reserves may be established to protect entire habitats, only five small reservations have been established to date (as “wilderness areas” as mentioned above), owing to reluctance on the part of land-owners to cooperate with the MOE to protect endangered species on their land (Yoshida 2004: personal communication). In addition, the law has been criticised by conservationists for putting excessive emphasis on protecting individual species rather than ecosystems in general (e.g. Yoshida 2004: personal communication; Domoto 1997). This is reflected clearly in the nature and purpose of the reserves, which focus on the management of one species and its habitat, rather than an ecological system comprised of a complex network of interacting organisms.10

In 1995, subsequent to Japan becoming a signatory to the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1992, the National Biodiversity Strategy, which outlined the basic principles for conserving biodiversity, was introduced. However this too has been criticised for lacking quantitative targets and not adequately addressing the management of wildlife and their habitats outside protected areas (OECD 2002: 29). In addition, the preservation of biodiversity is not reflected in the management of national parks, in which development and human activity impacting on the natural park environment is poorly controlled and regulated and wildlife and their habitats are not well monitored and protected (Ishikawa 2001: 201).

While recent legislation heightens the profile of nature conservation and its importance, it remains largely ineffective without adequate staff, skills and resources to carry out effective wildlife management programmes. Central and prefectural (regional) government budgets for wildlife management are limited and wildlife management operations are significantly understaffed. Furthermore, very few of the staff employed by the MOE or prefectural governments are specialists in wildlife conservation or even trained in this field (Miyai Roy 1998; Hazumi 2006). Thus, there is a significant gap between legislation and implementation with regard to the nature conservation function.

The function of national parks in nature conservation

It is generally expected that one of the key purposes of national parks is to protect natural environments of scenic and ecological value and the wildlife within them. However a number of authors (e.g. McGill 1992; Natori 1997; Ishikawa 2001) have suggested that in Japan, the designation of areas of “ecological significance” as a national or natural park, far from affording areas increased protection, often proves detrimental to the conservation of the area, owing to such factors as the development of tourist facilities, road construction, vehicle pollution and over-use.

An overview of the history of national parks in Japan serves to provide context for this apparently paradoxical situation. Japan’s first law establishing national parks was the National Parks law, which came into force in 1931, with the first national parks being established in March 1934. National parks were established with the purpose of promoting recreational activities and aiding the development of tourism, particularly after the Second World War. As a result, the definition of “national park” became ambiguous as national parks included scenic areas, tourist resorts, and suburban recreational areas. To deal with this problem, the National Parks Law was revised in 1949, and national parks were designated according to more rigorous criteria. Any area which did not meet the criteria was designated as a quasi-national park. In 1957, the Natural Parks Law was enacted, establishing regulations for the various national parks, and forming the basis of the current natural park system (see Table 1). From the late 1950s onwards, Japan entered a period of high economic growth, and as income per capita rose, visitors to natural parks increased sharply. Requests from prefectural or local governments to designate scenic areas in their regions as national or quasi-national parks also intensified, and areas designated as new quasi-national parks or incorporated into existing national parks increased. Currently there are 29 national parks, totalling an area of 2.09 million hectares (5.5 per cent of the area of the country) and 56 quasi-national parks, occupying 1.36 million hectares (3.6 per cent of the area of the country) (MOE 2008a). A further characteristic of the national park system which does not lend itself to nature conservation is the system of jurisdiction over parks. Unlike many countries where national parks are comprised of state-owned land designated solely for recreational and conservation purposes, in Japan, a significant proportion of the land in national (or natural) parks is either privately owned or under the jurisdiction of a government body other than the MOE (MOE 2008b).

As noted, the emphasis of the Natural Parks Law is the stimulation of tourism, and it explicitly allows for the development of tourist facilities in areas designated as national or natural parks (Natori 1997: 552). Further exacerbating the lack of protection for natural parks, in 1987 The National Resort Law was enacted, as part of the government’s plan to encourage tourism development. Clause 15 of the law specifically provides for the opening up of state-owned forests as resort areas (Yoshida 2001; McCormack 1996: 87–88). As a result, much of the area designated as natural parks is heavily developed with roads, houses, golf courses and resorts (McGill 1992; Ishikawa 2001: 67–109). A park demonstrating the impact of this process is Shiga Heights, habitat to the famous snow monkeys. Before it was designated a national park, tourist facilities consisted of one hotel and a few natural ski slopes. By 1987, it had 22 ski resorts and 101 hotels, and attracted many times more visitors than previous to its designation (Stewart-Smith 1987: 68–69).

Furthermore, the Natural Parks Law does not limit visitor numbers to parks: some national parks experience visitor numbers of more than 10,000 per day at popular times of the year (Ishikawa 2001: 198). To facilitate tourism, alpine tourist routes have been developed, beginning with the opening up of the Tateyama-Kurobe Alpine Route in Chūbu Sangaku National Park in 1971. Concomitant with high visitor numbers is the risk of damage to the environment caused by the disposal of large volumes of human waste, trampling of fauna by visitors, littering, and vehicle exhaust emissions. For example, exhaust emissions from the large number of tourist buses which travel the Tateyama-Kurobe Alpine Route in northern Honshu is reported to have caused damage to the beech forest along the route (Ishikawa 2001: 199). In addition, authorities may carry out additional development to improve safety, convenience, or access for tourists. An example is levee works in the Azusa River, at the entrance to Chūbu Sangaku National Park. The Ministry of Transport proceeded with the works—despite their potential impact on the surrounding environment—in order to protect tourists in the event of the river flooding (Ishikawa 2001: 198–199).

It has been suggested that Japan’s natural park management policy unduly emphasises the preservation of scenic beauty, with little regard for ecological preservation (Natori 1997: 552; Ishikawa 2001: 196–198; McCormack 1996: 96). A case which exemplifies this emphasis on the preservation of scenic beauty is that of the Shihoro Kōgen road. The local government of Hokkaido first proposed a plan to construct a tourist highway through the Daisetsusan National Park (the largest national park in Japan) in 1965. The construction initially went ahead but was halted in 1973. The project was proposed again during the resort-boom of the 1980s. Opposition temporarily halted the project, but in 1995 the Environment Conservation Council accepted a modified plan which involved digging a massive tunnel through the mountains. The revised plan met the criteria of the Natural Parks Law which prohibits construction that damages the visual landscape of a national park, but does not prohibit projects which will cause ecological damage which is “unseen”. Finally, however, in 1999, following vigorous campaigning of national and local environmental organisations, the Governor of Hokkaido announced that the project would be shelved (Yoshida 2002).

A further weakness of the Japanese natural park system is that the Ministry of the Environment (formerly the Environmental Agency) does not have sole jurisdiction over these areas. Twenty-six per cent of national park land and 40 per cent of natural park land is privately owned. In addition, of the 62 per cent of national park land, and 46 per cent of natural park land that is state-owned, much of this is under the primary jurisdiction of the Forestry Agency or other agencies with industrial or economic interests in the land. Conflicts of interest between the Ministry of the Environment and agencies which have an economic interest in a park (for example, through mining and forestry) are not uncommon, further compromising the conservation function of natural parks.11 An example of this is the Shiretoko logging case, where the Forestry Agency’s core objective, to generate income from forestry, clashed with the interests of nature conservation.12

Another problem relating to the management of national parks is inadequate staffing. In Japan, there is approximately one full-time staff member per 10,000 hectares, in comparison to one staff member per 1,500 in the United States or one per 2,000 hectares in the United Kingdom (Ishikawa 2001: 203). This means that while staff are, in theory, responsible for wildlife management duties such as protection and breeding programmes for designated species and the management of wildlife protection areas in accordance with the Law for the Conservation of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (1992), they are actually preoccupied predominantly with administrative duties such as processing permits. With staff overburdened, other duties such as environmental surveys, monitoring activities and conservation education rely predominantly on volunteers (Ishikawa 2001: 199–200).

Exemplifying these problems is Izu national park. Although the Izu archipelago is designated as a national park, with several sites designated as “special protected areas”, there are few rangers, and loss of habitat continues on many islands (Birdlife n.d.). In addition, owing to low staff numbers, staff are rarely able to ensure compliance with the conditions of use in park zones: for example, ensuring that the public does not enter specially protected zones, or that prohibited activities such as hunting, lighting of fires and vehicle use do not occur. Another case exemplifying these issues is an area in the Shirakami mountains in northern Honshu, which encompasses the largest virgin beech forest in Japan and which has been designated a world heritage site by UNESCO owing to its unique flora and fauna. It is one of the ten designated “nature conservation” areas in Japan, of which there are only 21,500 hectares in total (0.05 per cent of Japan’s land area). However, owing to inadequate monitoring or education, visitors leave garbage in the forest, light fires, and enter specially protected areas where entry is prohibited (Kuroiwa 2002). The inability to monitor park use at this fundamental level inevitably undermines the effectiveness of parks as nature conservation areas.

As can be seen, an array of problems undermines the conservation function of national parks in Japan. A key weakness arises from the fact that natural parks from the outset have emphasised tourism development and the preservation of areas for their scenic, rather than ecological, value. Further, the conservation function of parks is undermined by the fact that park lands are not exclusively state-owned, and even in cases where they are under the jurisdiction of the state, this is often under government bodies which have economic or industrial interests in the use of park lands. This leads to conflicts between nature conservation interests and development, forestry, and private interests. Furthermore, until recently there has been no law requiring environmental impact assessments to be carried out before development occurs in national parks (or any other area of ecological significance for that matter).13 In the past, attempts have been made by the Environmental Agency (now the MOE) to strengthen the law governing the establishment and management of national parks, but these have been thwarted by the Forestry Agency and the former Ministry of Construction (now part of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport), which did not want their powers to manage the parks weakened (Natori 1997: 555).

Conflict between development and conservation

A recurrent theme, particularly during Japan’s high growth period, but still apparent today, is the conflict between development and conservation. Where there is a conflict between habitat protection and development, more often than not, the latter has prevailed. This is due to a multitude of factors: the relative power of pro-development government bodies such as the Ministry of Construction (now the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport), which have close ties to financially influential private corporations; the relative weakness of the MOE; a weak legislative framework for the protection of wildlife and their habitats; a relatively small and uninfluential nature conservation lobby; low public awareness of conservation and ecological issues; and a desire for development in order to stimulate regional rejuvenation.

A case which exemplifies this conflict is that of the miyako tanago (metropolitan bitterling), a freshwater fish now found only in the waters of the Kanto plain. In the early 1990s it was reported that the freshwater brooks and ponds in which these fish spawn were drying up due to the building of resorts and golf courses—which diminish the land’s capacity to store water—and the building of concrete outflows on farmland (Anon. 1994: 14). In addition, due to water pollution, there has been a marked decline in the matsukasagai, the shellfish in which the bitterling lays its eggs, employing it as an “incubator” (Kondo 1996: 9). However, farmland improvement and the development of resorts and golf courses were deemed important to local residents, and preserving the unique ecology of the metropolitan bitterling did not attract widespread public support. Finally in December 1994, in accordance with the Law for the Preservation of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, the Environment Agency designated the sole remaining bitterling habitat in Otawara as a protected sanctuary (Kondo 1996: 9). While undoubtedly this is a positive development, the striking fact is that measures to protect the bitterling’s habitat were only taken when only one habitat remained.

Another instance of the clash of development and conservation is the case of the Amami black rabbit (Pentalagus furnessi). The case exemplifies problems which are common to many rural areas in Japan, where human populations are both diminishing and aging, and where the local economy and employment opportunities are in decline. The Amami black rabbit is an endangered species endemic to the southern Amami Islands (there are estimated to be only 1,000 rabbits remaining). In the 1990s, its habitat was threatened by the proposed development of a golf course, which locals hoped would reinvigorate the local economy. Finally, after much protest, an environmental organisation successfully used the media to draw attention to the plight of the rabbit, and the Ministry of Culture subsequently halted the golf course (Domoto 1997).

It is also common for development projects or commercial activity to be pursued in areas of known ecological importance, despite potentially damaging ecological impacts. This is in part due to a lack of effective environmental impact assessment procedures, though perhaps more critically, it stems from the political and economic imbalance between pro-conservation and pro-development forces. One such case is that of the logging of the Shiretoko National Park in Hokkaido. It was well documented that the area is habitat to seriously threatened species such as Blakiston’s fish-owl, the White-tailed eagle and the Pryer’s woodpecker, as well as being the sole remaining habitat of several other species. Nevertheless, in 1986, the Forestry Agency announced a plan to selectively log 10,000 trees in an area of 1,700 hectares in the park. (Logging and other commercial activities in national parks are permissible under the Natural Park Law.) In spite of nation-wide opposition as a result of an organised and well-publicised campaign opposing the logging, the Forestry Agency proceeded with the plan in 1987.

The Isahaya Bay tidal-land reclamation project in Nagasaki Prefecture is another example of a project in which development objectives were placed ahead of environmental, and perhaps more ironically, economic considerations. It was carried out despite the fact that the original reason for the project had lost all relevance—to reclaim land for farming, at a time when Japan was experiencing an over-production of rice, and farmers were being paid to keep fields fallow (Lies 2001)—and in the face of widespread national and international opposition.

The mutsugorō became emblematic of all the creatures endangered by the Isahaya reclamation project (source).

Tidal-lands are vital buffers between the land and sea and are habitats supporting high biological diversity. The Isahaya Bay tidal land was also an important stopover point for birds migrating between Siberia and Australasia. It made up six per cent of Japan’s remaining tidal-land, and was habitat to about 300 species of marine life, such as the mud-skipper (mutsugorō), and approximately 230 different species of birds, including a population of Chinese black-headed gulls, of which only 2000 are estimated to remain worldwide (Umehara 2003).

A section of the 7 km long sluice-gate across Isahaya Bay

The project entailed the construction of a seven kilometre long dyke to cut off the tidal area in order to create flood-pools and 1,500 hectares of farmland. The government refused to review the project, despite repeated petitioning by local fishermen to halt the construction of the dyke and formal protests of over 250 organisations, both international and national. It was estimated that by the time the project was completed, each hectare of reclaimed land would have cost the tax-payer US $1.3 million. On the other hand, environmentalists claim that the project has resulted in the local extinction of a number of species, including many endangered species, such as the mud-skipper, in addition to destroying Japan’s largest remaining tideland habitat (Anon. 2002; Watts 2001; Crowell & Murakami 2001; Fukatsu 1997: 26–30; McCormack 2005).

In spite of the destruction already caused to island and coastal ecologies in Japan, particularly in the Okinawan archipelago, the government has pursued further development projects on other islands. One proposal, promoted for over a decade by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (which has administrative jurisdiction over the Ogasawara archipelago) was to construct an airport on Anijima, an island in the archipelago. The island is often called the “Asian Galapagos”, and is the home of primeval nature and Ogasawaran biota remaining only on Anijima. The airport was to include an 1800 metre runway to service a burgeoning tourist industry. Finally, after an independent environmental review was completed which clearly showed the extent of the environmental impact of the project, the Tokyo Metropolitan government shelved the plan, instead proposing to build the airport elsewhere on the archipelago (Tomiyama & Asami 1998; Guo 2009).

Conclusions

This paper provided an overview of the state of natural environments and wildlife in Japan today, and of the primary threats to these. Habitat destruction represents the greatest single threat to Japan’s wildlife and natural environments, and it continues in various forms, threatening to destroy more of Japan’s last remaining wetlands and natural and primeval forest. In addition, failure to adequately protect or monitor areas of ecological importance such as national parks exacerbates the problem.

The paper examined the key factors contributing to these threats to the natural environment. The first factor noted was the limited and relatively weak legislative framework and the gap between policy and implementation with regard to nature conservation and wildlife management. The second factor was a natural park system which emphasises tourism over the ecological value of parks, and a situation in which parks are not adequately monitored and protected against detrimental environmental impacts—whether as a result of tourism or development. The third, and possibly most critical, factor is the conflict between development and conservation: the imbalance in economic and political power in Japan means that, in general, where forces of development and conservation are at odds, forces for development prevail. Many of these factors exist in other countries facing challenges to the natural environment. The combination of such factors in Japan has nevertheless resulted in a far-reaching assault on the environment.

Given the pervasiveness of these underlying factors, the outlook for Japan’s remaining natural environments appears bleak. However, recent developments, such as an economy which has slowed considerably since the high growth period of the 1980s and early 1990s when development projects were pursued irrespective of the economic and environmental costs; a long-term demographic downturn; a strengthening environmental NGO (non-governmental organisation) sector; a change of government from the long-serving traditionally pro-development Liberal Democratic Party to the Democratic Party of Japan;14 and an increasing emphasis, both nationally and internationally, on the preservation of the earth’s remaining biodiversity, mean that there should be scope for (albeit restrained) optimism in regard to the prospects for the future of Japan’s natural heritage.

Catherine Knight is an independent researcher, who is employed by day as an environmental policy analyst. Her research focuses on New Zealand and Japanese environmental history. Her doctoral thesis explored the human relationship with the Asiatic black bear through Japanese history [available here. She is particularly interested in upland and lowland forest environments and how people have interacted with these environments through history. Her publications can be viewed here. Catherine also runs an online environmental history forum which explores New Zealand’s environmental history.

Recommended citation: Catherine Knight, "Natural Environments, Wildlife, and Conservation in Japan," The Asia-Pacific Journal, 4-2-10, January 25, 2010.

View Article in The Asia-Pacific Journal

24.01.2010, 02.17

24.01.2010, 02.17

Susumu Inamine, center, celebrated with his supporters as he was virtually assured of his victory in a mayoral election for the Okinawan city of Nago on Sunday. Kyodo News, via Associated Press

Susumu Inamine, center, celebrated with his supporters as he was virtually assured of his victory in a mayoral election for the Okinawan city of Nago on Sunday. Kyodo News, via Associated Press